Has the time come for Caribbean Republics?

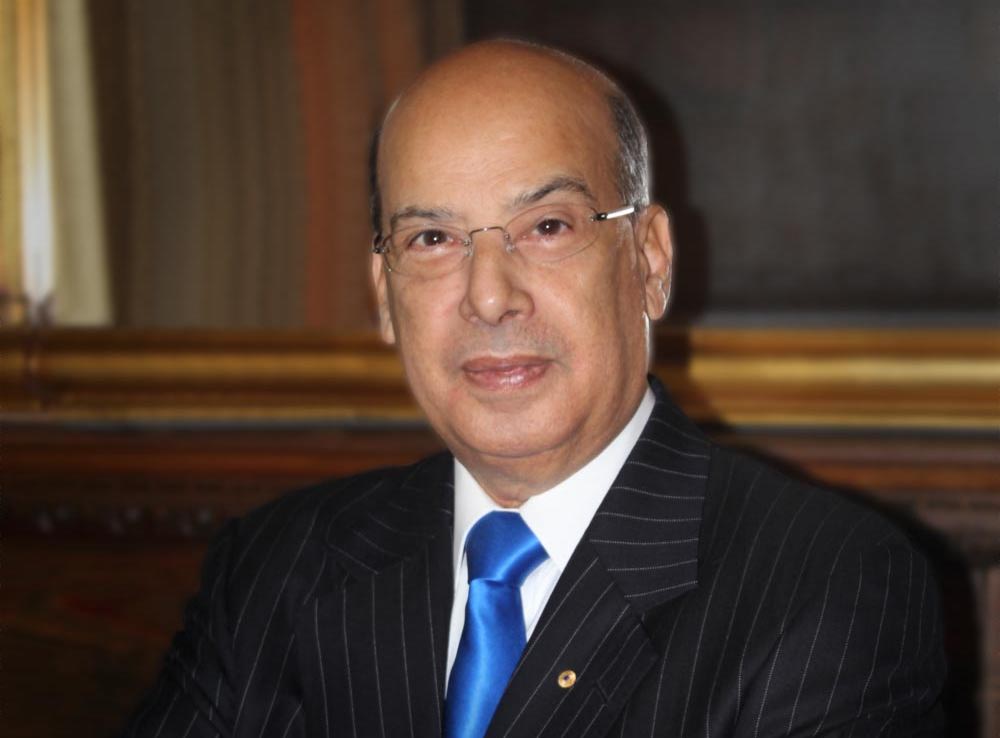

Article by Sir Ronald Sanders

(The writer is Ambassador of Antigua and Barbuda to the United States and the Organisation of American States. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London and at Massey College, University of Toronto. The views expressed are entirely his own.)

In 1994, shortly after Antigua and Barbuda and Cuba established diplomatic relations, Fidel Castro and Antigua and Barbuda’s Prime Minister, Lester Bird, had a memorable conversation in Havana.

The conversation is worth recalling in the context of the third announcement by a Government of Barbados that by November 2021, it intends that Barbados should be a Republic, shedding monarchical status and Queen Elizabeth II as Head of State.

The conversation between Lester and Fidel, at which I was present as a member of the Antigua and Barbuda delegation, started with the revolutionary Cuban leader asking Lester (now Sir Lester) what big plans he had in mind for Antigua and Barbuda. Lester told Fidel that he was contemplating moving to make Antigua and Barbuda a Republic, relinquishing the monarch as the country’s Head of State.

Fidel’s response stopped Sir Lester and the entire Antigua and Barbuda delegation in our tracks. “Why?”, asked the legendary revolutionary. “Does she interfere with your government?”. Sir Lester explained that she did not and that, in a real sense, while Antigua and Barbuda like many other Caribbean countries was one of the Queen’s realms, her role in the government of the country was performed by a local representative and, apart from assenting to legislation which could not be withheld, was only ceremonial, having no executive authority.

“In which case”, Fidel responded, “you might consider remaining as you are. The Queen doesn’t interfere with your government and she provides to foreign investors and others a level of confidence in the constitutional arrangements of your state”.

The surprising conversation did not go much beyond that. It was staggering to the Antigua and Barbuda delegation, but it demonstrated the practical sense of Fidel Castro, which might account, in part, for the survival of Cuba despite the punishing embargo by the United States.

That 1994 conversation between Fidel and Sir Lester took place at least nine years before Owen Arthur, as Prime Minister of Barbados, first proposed Republican status for Barbados in 2003; eighteen years before Jamaican Prime Minister, Portia Simpson suggested it in 2012; twenty-one years prior to Prime Minister Freundel Stuart echoed the proposition in 2015 for Barbados; twenty-two years before Andrew Holness as Prime Minister repeated it in 2016 for Jamaica; and twenty-six years before the latest announcement by the Barbados government of Prime Minister Mia Mottley on September 15.

So far, none of the countries in which this proposal has been made has gone through with it.

While the Throne Speech, in which the most recent Barbados announcement was made, referenced Barbados’ first Prime Minister, Errol Barrow, cautioning against “loitering on colonial premises”, there would be many who would draw a distinction between seeking independence from the colonial authority of the British (which was the context of Barrow’s remarks) and retaining Queen Elizabeth II as Head of State.

Both Owen Arthur and Freundel Stuart might have retreated from the idea not because they did not believe it to be right, but because within the Barbados society, including the business community, a great value is placed on the Queen as a symbol, if nothing else, of stability and maybe even of unity above the fray of politics.

This is probably true, too, in the case of the Bahamas, Belize, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, and the five other independent countries of the Eastern Caribbean where the Queen is still head of state.

In the event, the present government of Barbados has the greatest chance of success in achieving the objective of becoming a Republic by next year. Unlike the remaining independent countries of the Caribbean of which the Queen is head of state, the Barbados constitution allows for this significant change in constitutional status by “votes of not less than two-thirds of all the members of the House”. No referendum of the electorate is required. Given that the present Mottley Government controls twenty-nine of the thirty seats in the House of Assembly, achieving the vote should be easy.

The one obstacle would be how intense, if at all, will be resistance by elements of the Barbados society and the business community against the idea, and how much it threatens to divide the country. This was a matter that clearly influenced both Arthur and Stuart, during their premierships, not to press ahead with the idea.

Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Jamaica and the other six independent Caribbean countries require not only a two-thirds majority in the House of Representatives, but also a majority vote by the electorate in a referendum.

Winning referenda in the Caribbean has proven to be as difficult as pushing a boulder up a mountain. In 2009, a referendum in St Vincent and the Grenadines rejected the proposal to oust the monarchy and substitute it with a republic. And, several referenda have failed in other Caribbean countries to alter the Constitution to allow the Privy Council to be replaced by the Caribbean Court of Justice, signifying a reluctance by the majority of the electorate for radical change.

While becoming a Republic is regarded by Caribbean intellectuals as “rounding the circle of independence”, the argument is not as much about the head of state not being a white woman living in a distant former colonial power; it is more about confidence in good governance when institutions perceived as beneficial are changed.

That argument can only be won by political parties in every Caribbean country, demonstrating that they will maintain the rule of law, civil and political rights, and democratic principles, including non-discrimination particularly in race and religion.

However much ruling political parties might wish to join the Barbados government in pursuing republican status, “the matter is really in the hands of the Caribbean people” as the Queen said in 2012 when Portia Simpson declared: "I love the Queen, she is a beautiful lady, and apart from being a beautiful lady she is a wise lady and a wonderful lady. But I think time come".

Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com