Covid-19 and its consequences for Caribbean diplomacy

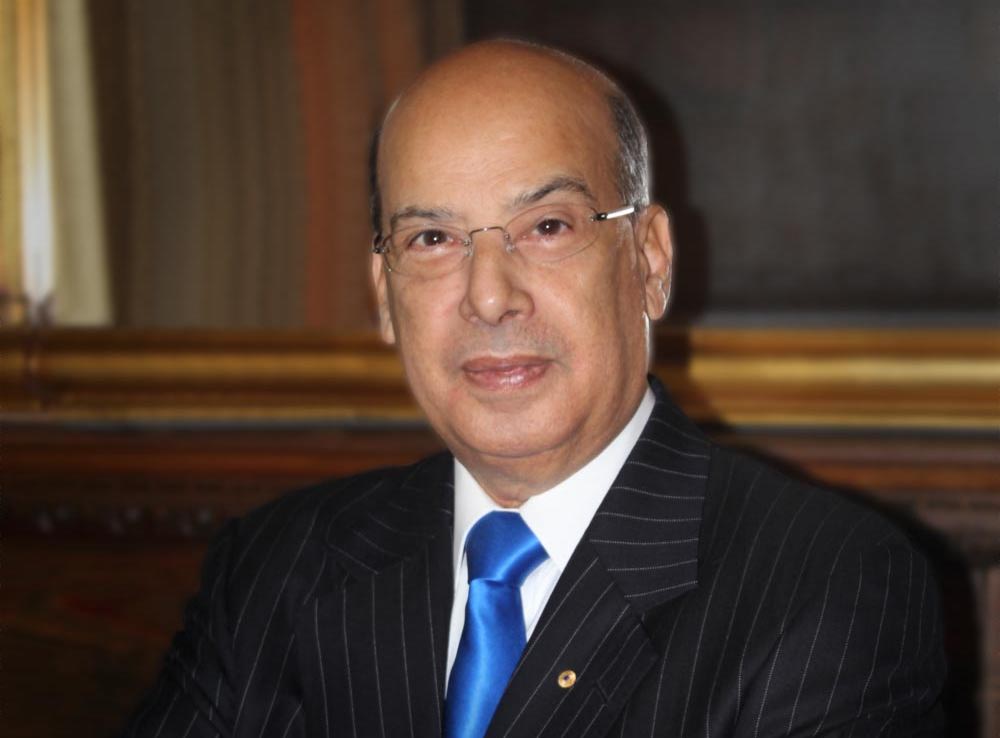

Article by Sir Ronald Sanders

(The writer is Ambassador of Antigua and Barbuda to the United States and the Organisation of American States. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London and at Massey College, University of Toronto. The views expressed are entirely his own.)

The COVID-19 pandemic is severely limiting the work of diplomacy. It could have a lasting adverse effect on international relations if finding a vaccine continues to elude global researchers for much longer.

Critical to the work of diplomacy, at every level, is interpersonal contacts at which relationships are forged, attempts are made to iron-out differences, or, at least, some deal is struck – even if it is to defer divisive decisions.

But the protocols of managing the coronavirus has halted such contacts. Physical meetings and conferences have been replaced by constrained, strait-jacketed, virtual meetings. Restaurants, famous as venues for deal-making, are firmly shut. The result is that off the record discussions are simply not possible. There would be few in the diplomatic world who do not assume that telephone calls, and discussions on virtual digital platforms are not recorded – therefore as little as possible is said, constraining the possibility of compromise.

Since March, it has been impossible for diplomats in international organisations, such as the United Nations bodies and the Organization of American States (OAS), to conduct face to face meetings either in Councils or in one-on-one discussions.

In Washington, for instance, US government buildings, offices of members of the US Congress, and Embassies have been closed to the public with most officials and diplomats forced to work from home. Meetings, conferences, and bilateral discussions have had to be held on virtual digital platforms like Zoom and Kudo. But while these meetings are better than nothing, they are inadequate to the task of diplomacy much of which relies on interpersonal contacts.

The OAS now holds all meetings of its Permanent Council and Committees through a virtual platform. Subsequently, representatives make speeches at each other. Lost is the opportunity for dialogue that could help to bridge the divide between governments. Meetings lack spontaneity and flexibility. Often, they are interrupted by failures in technology.

The most significant injury to multilateral diplomacy is that diplomats cannot negotiate effectively by disembodied virtual means. For example, negotiating resolutions and declarations is a painstaking process in which every word matters. One word could change both meaning and intent. Therefore, great care is placed on the consequences of the use of a word to a country. As an example, the words “Climate Change” and “Global Warming”, much as they represent existence and survival to small states, conjure a different importance for industrialized countries, particularly those that deny the existence of both phenomena. The intense negotiations, required to reach an understanding, if not an agreement, on the use of these terms, are undercut by the restricted nature of online meetings.

One of the big challenges that the OAS will face in October is how to persuade foreign ministers from 33 countries to sit in front of their computers at home over two days to participate in the Organization’s General Assembly, its highest decision-making body. The meeting will be held in name, but its quality will be gravely undermined.

General Assemblies are more effective for the opportunity they provide for ministers to talk with each other outside the formal Council. It is in the corridors and in the lounges that problems are overcome, new relationships are forged, and old ones strengthened. There will be no such opportunity this year. Indeed, a raft of new foreign ministers, including three new ones from Guyana, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago, will not have the chance to meet their counterparts from the US, Canada, and Latin America.

The problem is also acute at the United Nations both at the levels of the Security Council and the General Assembly. Up to July, the Security Council could not vote on important issues because its rules do not allow for such voting at informal meetings which is how virtual meetings are characterized.

Recently, representatives have gathered physically once a week to vote on some important issues, but, even so, the work of the Security Council is greatly delayed and impaired. Significantly, this has suited the bigger powers that have taken advantage of Security Council paralysis to advance their national positions, and even their rivalry.

Similarly, in the UN General Assembly, no formal electronic voting system has been established because some members still resist it. Consequently, resolutions can only pass by consensus of all member states. Since such consensus cannot be negotiated, only minimal compromises are made. That, too, suits the few giant nations, long intolerant of the many dwarf countries.

All of this makes the world a less safe place. It provides the opportunity for powerful countries, which have the capacity for non-commercial travel, to make arrangements with other countries, outside of the multilateral system. Invariably, these arrangements serve the interests of the more powerful government.

There is no question that meetings held on virtual platforms have proven that they are beneficial for some purposes. If they continue, they will save governments and businesses a great deal of money that, hitherto, had been spent on travel and accommodation. They should be retained for routine meetings on non-controversial issues.

But for hard-bargaining and on matters that require careful negotiation, virtual meetings are unhelpful to diplomacy whose effectiveness depends on interpersonal contacts, building relationships and the ability to explore possibilities that are not formally on the table.

Small states, like those in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) are being left out – and left behind. Unlike powerful states, they need a functioning multilateral system in which to represent their interests – right now that system is fractured even more than it was prior to COVID-19.

The effects of the pandemic have limited the diplomacy of Caribbean state, including their capacity to negotiate with the nations whose policies most greatly affect them.

This situation calls for more cohesive policies by CARICOM governments and collective action by all of them in every international organisation.

Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com