Climate Change killing the Caribbean one cut after the other

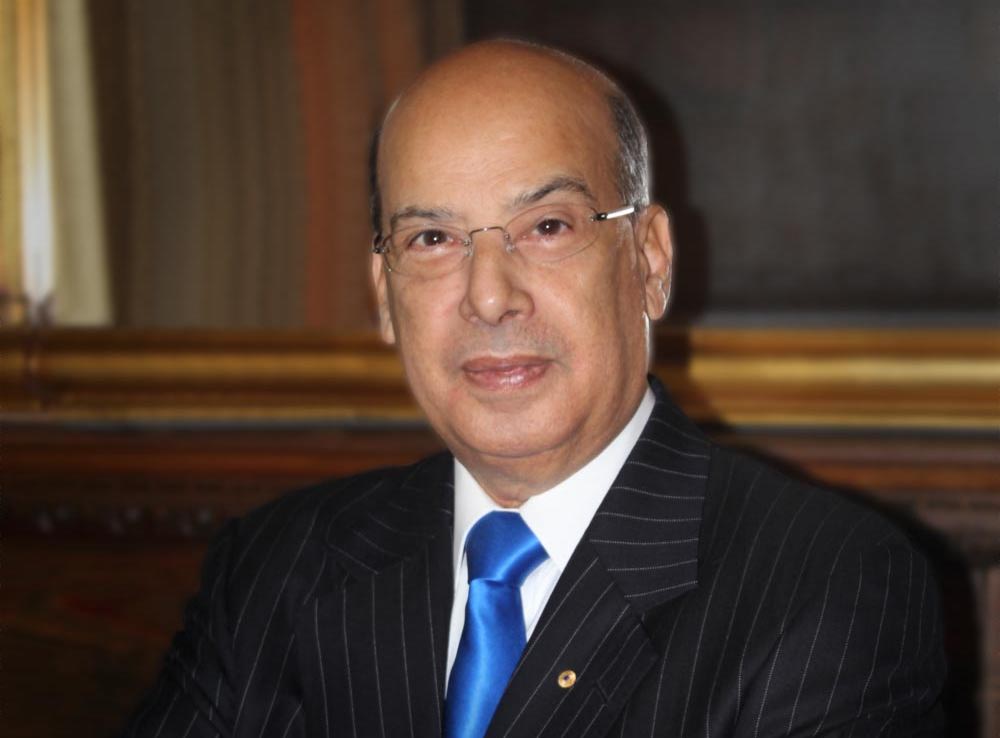

Article by Sir Ronald Sanders

(The writer is Ambassador of Antigua and Barbuda to the United States and the Organisation of American States. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London and at Massey College, University of Toronto. The views expressed are entirely his own.)

Amid the feverish work to cope with both the public health and economic effects of COVID-19 on their populations, Caribbean governments can be forgiven for dropping their guard against the existential dangers posed by Climate Change.

But their guard must be raised again. The dangers are enlarging; they need continuous and comprehensive attention, as the present hurricane season reminds.

The difference between the COVID-19 pandemic and Climate Change, is that while the circumstances that the disease has engendered seem interminable, they will pass or be significantly improved in the medium term, but the effects of Climate Change are set to worsen for a very long time.

Reports indicate that the planet could see a greater temperature increase in the next 50 years than it did in the previous 6,000 years combined. Recent studies show that today, one percent of the world is a hot zone, in which life is barely possible. It is now projected that, by 2070, that figure will rise to 19 percent.

Fifty years from now might seem far away, requiring no immediate action. However, the destruction of global warming and sea-level rise, scientifically linked to Climate Change, is accretive. While in 2070 its impact will be grave, in each year, until then, it will affect almost every aspect of human life negatively and severely, in a gradual build-up. And, each year, crucial productive sectors of Caribbean economies will be steadily eroded, including agriculture, fisheries, and tourism.

Consequently, farming communities will be driven off land that will either cease to be arable, or that are subjected to such rapid extremes of weather that crops are destroyed year after year. This pattern has already emerged in Central America, causing migration of farmers both within countries and across borders. The refugees, who have been desperately trying to enter the United States through its southern border, are living testimony to climate disruption.

On July 23, ProPublica and The New York Times Magazine, published an article on Climate Migration, which chronicles the large number of people, particularly farmers, across the world who have become refugees. The publication cites a 2108 World Bank report that says, if nothing is done, by 2050 “there will be 143 million internal climate migrants across three regions of the world”. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the figure could reach as high as 17 million. The Caribbean has already witnessed such refugees – Dominica, continuously since 1979; Antigua and Barbuda in 2017; and The Bahamas in 2019. Fortunately, these refugees could be accommodated within national boundaries or in neighbouring countries; the doors to other countries were locked.

This phenomenon flags up the big issue of our time. Rich countries are among the largest contributors to global warming and sea-level rise, causing migration and refugees. Yet, many of them across the world – the United States in North America; Britain, France and Italy in Europe, and Australia in the Pacific – are paying lip service to providing funds to help affected countries, while closing their borders to migrants. As this trend continues, Caribbean migrants will have no place to go.

The effects of global warming over the last five decades have been devastating agricultural production. CARICOM countries, except for Belize and Guyana, are now net food importers. At least seven of the 14 countries import more than 80 percent of the food they consume, resulting in the region’s annual food import bill estimated in 2019 at US$5 billion.

This serious vulnerability has been alarmingly exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, as the foreign exchange earnings of countries have diminished. Stark choices have had to be made about foreign purchases. Should the priority be medicines, food, or building materials? This has caused governments to encourage more local food production.

However, these belated efforts in agriculture will be frustrated, if not overturned, by uncurbed climate change. Extreme heat, droughts, floods, saltwater encroachment due to rising sea levels and storms have harmed agricultural productivity and caused food price hikes and income losses. These events have wiped out crops, bankrupted farmers and forced them out of business, in many cases permanently. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, crop yield declines of 10-25 percent may be prevalent by 2050 because of climate change.

The effects on tourism would also be devastating. Suffice to say, that the challenges and dangers posed by global warming and sea-level rise are enlarging, requiring strenuous and sustained responses at the national, regional, and international levels.

Even now, there should be a joined-up effort by national government agencies to factor the effects of climate change into their economic planning. That planning should be advised by scientific research and data. National blueprints should also dovetail into a regional action plan. Integral to the plan should be coordinated international advocacy about the Caribbean plight.

In Washington, DC, CARICOM ambassadors have started an international outreach by soliciting the convening power of the Organization of American States (OAS) and its Secretary-General, Luis Almagro. The idea to which Almagro has given full support is to gather the leading financial and development institutions to consider actions to save the Caribbean from the catastrophic consequences of unrestrained climate change. There is good reason to give the Caribbean special attention; it accounts for less than one percent of global greenhouse gas emissions and suffers hugely disproportional impacts.

Actions, like that taken by the OAS secretary-general, should be secured from other heads of multilateral institution such as the Commonwealth of which Caribbean countries are members.

Since 2010, more than 30 studies, aimed at quantifying the economic impacts of climate change on various vulnerable sectors of the Caribbean. have been conducted. Therefore, the nature and scope of the problem are well-known; it is time to stop the studies and to start the action.

In the words of the poet Dylan Thomas: “Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight; rage, rage against the dying of the light”. And do so from the rooftops of the world.

Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com