A tale of two neighbours

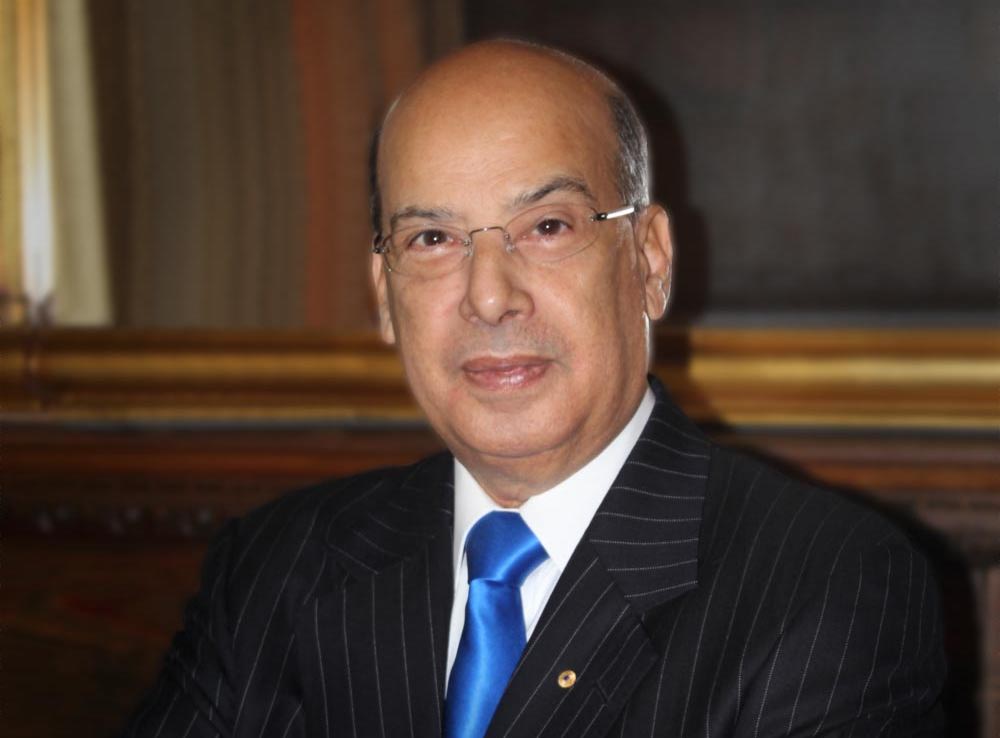

Article by Sir Ronald Sanders

(The writer is Ambassador of Antigua and Barbuda to the United States and the Organisation of American States. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London and at Massey College, University of Toronto. The views expressed are entirely his own.)

Recent electoral events in Guyana and Suriname, which border each other on the north-eastern coast of the South American continent, display a remarkably different approach to democracy that could be the determining factor in catapulting Suriname’s development and prosperity well ahead of Guyana’s.

The two countries have many similarities and some differences.

One of the principal differences is that Suriname endured coup d’états by the military, whereas Guyana has not, although the latter is notorious for disputed elections with losing parties accusing the governing party of rigging the elections. There is a twist in the latest elections, held in Guyana on March 2, 2020. After all parties and observers declared the elections to be free and fair, the governing party, APNU-AFC, claimed that the opposition party, the PPP/C had somehow fixed the elections.

The coup d’états in Surname were both led by Desiré Delano “Dési” Bouterse, who became the de facto leader of the country from 1980 to 1987, and then again from December 1990 to May 1991.

Bouterse, eventually won two terms in office by way of the ballot box from 2010 to 2015 and 2015 until May 25, 2020, when his National Democratic Party lost elections.

As elections in these two neighbouring states were approaching at the beginning of 2020, if any public polling were taken on which government would have refused to leave office, even if it had clearly lost, it would have undoubtedly reflected Bouterse’s. After all, a man who had twice seized power at the point of a gun was a superior candidate for discarding the will of the electorate, democratically exhibited in elections.

Not so. In the end, the Suriname elections result was declared on June 4, and Bouterse conceded to the opposition parties, led by Chandrikapersad ‘Chan’ Santokh of the United Reform Party. Bouterse himself placed the presidential sash of office on Santokh at a ceremony on July 16.

In the meantime, the declaration of the result of the Guyana elections has been prolonged for over four months. A constant cycle of appeals to the Courts by supporters of the APNU-AFC now halt a result being declared. Even after the highest Appellate Court, the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), pronounced on the matter, appeals have been made to lower courts to overturn the CCJ’s judgement – an act unprecedented in the history of global judicial systems.

A striking similarity about Guyana and Suriname is that they have both become beneficiaries of major finds of oil and gas that promise to place them amongst the richest countries in the Western Hemisphere. The revenues from oil and gas sales would transform them from backwater nations to countries, whose economic power would make them significant influencers in the Caribbean and the hemisphere.

But, there is a corollary to that observation. It is that Suriname and Guyana each has to be an acceptable state in the world community, with governments that demonstrably adhere to democracy and the rule of law. The days of rogue governments operating with impunity in the international community are over.

There are several mechanisms by which Suriname and Guyana are tested. These include the CARICOM Charter of Civil Rights, the Inter-American Democratic Charter in the Western Hemisphere and the UN-adopted International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Suriname has now demonstrated its readiness to honour its commitments under these binding agreements, giving its own people, the international community and investors in its oil and gas industry the confidence that, in moving forward, democracy and the rule of law will be respected.

Suriname has every prospect now of establishing itself as a leader-nation in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) utilising its new oil and gas wealth to help finance regional integration in crucial areas such as air and sea transportation; food security; providing concessional financing for development projects through the Caribbean Development Bank, and acting as a strong interlocutor for CARICOM in international affairs.

Guyana, on the other hand, once a strong leader and an important voice in regional and global affairs, risks being ostracised in the regional, hemispheric, and international communities.

No number of braggadocious political claims about Guyana’s ‘sovereignty’, and why it doesn’t need the United States, CARICOM, the Organization of American States, the European Union or any other country or international institution, changes the reality that Guyana does need a constructive and respected relationship with all of them.

For sure, there is a great deal of reform that is urgently required within Guyana to establish truly independent and sustainable institutions which reflect racial inclusion and balance in their composition, especially in their decision-making boards. Racial and religious understanding and appreciation must become integral to the education curriculum. Fear that the proceeds of revenues from oil and gas will be sequestered into the pockets of a few, or for the benefit of one racial group over another, has to be addressed by the adoption of laws governing transparency and wealth distribution and by severe penalties for their violation.

The electoral system also requires root and branch transformation, including by ensuring that no politician serves on the Elections Commission or appoints anyone to it – that task should be passed to representative bodies of civil society and enshrined in law.

But, more than anything else, those who seek political office should understand that they are elected to serve the nation, and not to become the nation’s overlords. And, when the majority of the electorate vote to relieve them of office, they should leave, recognising that political office is not their right to hold; it is the people’s right to give and to take away.

Bouterse of Suriname showed, in the end, that he understood well that Suriname’s interest in the 21st Century would have been gravely blighted had he chosen to remain despite the will of the people.

In this tale of two countries, adherence to democracy and the rule of law has set the Surinamese people on the path to progress, while the Guyanese people are being hobbled from striding forward on that rewarding road.

Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com